Nile Rodgers - The Stool Pigeon Interview

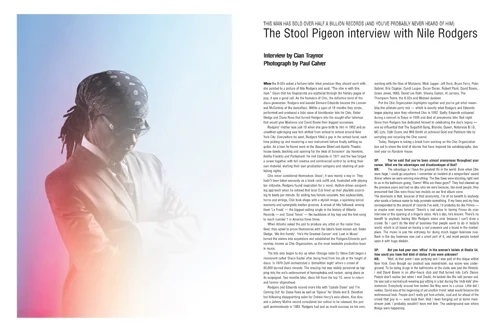

When the B-52s asked a fortune teller what producer they should work with, she pointed to a picture of Nile Rodgers and said, “The vibe is with this man.” Given that his fingerprints are scattered through the history pages of pop, it was a good call. As the founders of Chic, the definitive band of the disco generation, Rodgers and bassist Bernard Edwards became the Lennon and McCartney of the dancefloor. Within a span of 18 months they wrote, performed and produced a tidal wave of blockbuster hits for Chic, Sister Sledge and Diana Ross that turned Rodgers into the sought-after talisman that would give Madonna and David Bowie their biggest successes.

Rodgers’ mother was just 13 when she gave birth to him in 1952 and an unsettled upbringing saw him shifted from school to school around New York City. Everywhere he went, Rodgers filled a gap in the school band, each time picking up and mastering a new instrument before finally settling on guitar. As a teen he found work in the Sesame Street and Apollo Theatre house bands, backing and opening for the likes of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Aretha Franklin and Parliament. He met Edwards in 1971 and the two forged a career together with full creative and commercial control by writing their own material, starting their own production company and retaining all publishing rights.

Chic never considered themselves ‘disco’; it was merely a way in. They hadn’t been taken seriously as a black rock outfit and, frustrated with playing bar mitzvahs, Rodgers found inspiration for a novel, rhythm-driven songwriting approach when he noticed that local DJs lined up their playlists according to beats per minute. By adding two female vocalists, two keyboardists, horns and strings, Chic took shape with a stylish image, a sparkling lyrical economy and synergistic molten grooves. A streak of hits followed, among them ‘Le Freak’ — the biggest-selling single in the history of Atlantic Records — and ‘Good Times’ — the backbone of hip hop and the first song to reach number 1 in America three times.

When Atlantic asked the pair to produce any artist on the roster they liked, they opted to prove themselves with the label’s least-known act, Sister Sledge. ‘We Are Family’, ‘He’s the Greatest Dancer’ and ‘Lost In Music’ turned the sisters into superstars and established the Rodgers/Edwards partnership, known as Chic Organization, as the most bankable production team in music.

The hits only began to dry up when Chicago radio DJ Steve Dahl began a movement called ‘Disco Sucks’ after being fired from his job at the height of disco. In 1979 Dahl orchestrated a ‘demolition night’ where a crowd of 90,000 burned disco records. The ensuing riot was widely perceived as tapping into the era’s undercurrent of homophobia and racism, using disco as its scapegoat. Two months later, disco fell from the top 10, never to return and forever stigmatised.

Rodgers and Edwards scored more hits with ‘Upside Down’ and ‘I’m Coming Out’ for Diana Ross as well as ‘Spacer’ for Sheila and B. Devotion but following disappointing sales for Debbie Harry’s solo album, Koo Koo, and a Johnny Mathis record considered too radical to be released, the pair split acrimoniously in 1983. Rodgers had just as much success on his own, working with the likes of Madonna, Mick Jagger, Jeff Beck, Bryan Ferry, Peter Gabriel, Eric Clapton, Cyndi Lauper, Duran Duran, Robert Plant, David Bowie, Grace Jones, INXS, David Lee Roth, Sheena Easton, Al Jarreau, The Thompson Twins, the B-52s and Michael Jackson.

Put the Chic Organization highlights together and you’ve got what resembles the ultimate party mix — which is exactly what Rodgers and Edwards began playing once they reformed Chic in 1992. Sadly, Edwards collapsed during a concert in Tokyo in 1996 and died of pneumonia later that night. Since then Rodgers has dedicated himself to celebrating the duo’s legacy — one so influential that The Sugarhill Gang, Blondie, Queen, Notorious B.I.G., MC Lyte, Faith Evans and Will Smith all achieved Gold and Platinum hits by sampling and recycling the Chic sound.

Today, Rodgers is taking a break from working on the Chic Organization box set to share the kind of stories that have inspired his autobiography, due next year on Random House.

SP: You’ve said that you’ve been almost anonymous throughout your career. What are the advantages and disadvantages of that?

NR: The advantage is I have the greatest life in the world. Even when Chic were huge, I could go anywhere. I remember an incident at a songwriters’ award dinner where we were winning everything. The Bee Gees were standing right next to us in the bathroom going, ‘Damn! Who are these guys?’ They had cleaned up the previous years and had no idea who we were because, like most people, they presumed that Chic were those two models on our first album cover.

The downside is that, because of that anonymity, I’m of no benefit to anybody who wants a famous name to help promote something. If my fame and my face corresponded to the amount of records I’ve sold, I’d probably be like Prince — or maybe even more famous! There’s a real value to having Prince do your interview or the opening of a lingerie store. He’s a star, he’s known.

There’s no benefit to anybody having Nile Rodgers come over because I can’t draw a crowd. So I can’t do the kind of business that people seem to do in today’s world, which is all based on having a real presence and a brand in the marketplace. The music is just the entryway for doing much bigger business now. Back in the day business was just a small part of it, and most people looked upon it with huge disdain.

SP: But you had your own ‘office’ in the women’s toilets at Studio 54. How could you have that kind of status if you were unknown?

NR: Well, at that point I was partying and I was part of the clique within New York. Even though our product was mainstream, our scene was underground. To be doing drugs in the bathrooms at the clubs was just the lifestyle. I met David Bowie in an after-hours club and that turned into Let’s Dance. People don’t realise but when I met David, he looked like the odd person out.

He was just a normal suit-wearing guy sitting in a bar during the ‘club kids’ phenomenon. Everybody around him looked like they were in a circus. Little did I realise, David was at the beginning of yet another trend: what would become the metrosexual look. People don’t really get how artistic, cool and far ahead of the crowd that guy is — even back then. Had I been hanging out at some mainstream joint, I probably wouldn’t have met him. The underground was where things were happening.

SP: How would you describe the excess of the era for someone who wasn’t there?

NR: I think it was way over the top and out of control when I look back on it with the clarity I have now. The thing that made life a bit different was that AIDS was brand new and it felt like it was exclusive to the gay community. So we were in a world of open sex. It was common to meet a girl on an airplane and have sex right at your seat. Then you’d never see them again. It wasn’t because I was some superstar, because I wasn’t; that’s just how life was. So when tours were being planned we’d insist on flying certain airlines, even though it was more expensive, because they had the prettiest stewardesses. Most of the time they would end up being your girlfriend for the flight, sometimes afterwards as well. Those were the good old days, bro [laughs].

SP: What was the first sign that the party was over?

NR: It only hit us after our records stopped selling. When the ‘Disco Sucks’ movement happened, we didn’t think it would have any effect on us. If you listen to a disco record, it doesn’t sound like Chic. We had songs that worked at a disco but our records sounded more like instrumental R&B bands with hit songs. The thing that pissed us off was that because ‘Good Times’ was going up the charts at the same time as ‘My Sharona’, The Knack were labelled as the ultimate rock’n’roll band and Chic the ultimate disco band. Boy, did the industry get both of those wrong! [laughs]

Both records went to number 1 but The Knack never had another hit after that and neither did Chic. Interesting. When the smoke cleared, neither of us had a pot to piss in. Once that identity was forced upon us, we tried too hard to not be a disco band. All we had to do was our music and we would have been fine. Instead we allowed labels to get painted on us and it was almost like a smear campaign. When that happens, there’s nothing you can do. You’re helpless. It was one of those horrible situations where we were in the wrong place at the wrong time and so were The Knack. Thank God for Diana Ross. She rescued us.

SP: What did it take to repair your relationship with Bernard when Chic reformed?

NR: Playing with Bernard [laughs]. That’s all there is to it. Everything I’ve done with every other artist is some slight variation of my relationship with him. Either it’s some positive distortion or a negative one, but it’s still that same thing. When I turned 40, Bernard came to the China Club and Bruce Willis, Rick James and a whole bunch of people jumped up on stage. No matter how much of a jam we went into, the one thing that sounded amazing was how the guitar and the bass locked. That foundation was there that night: we were the guys behind the stars. That’s what we do. It finally sounded the way it was supposed to sound again.

SP: The night Bernard passed away, you were thrown out of your bed. What do you think happened?

NR: I’m a scientific sort of guy. All I can do is report what happened and you can draw your own conclusions. We were in Tokyo and I woke up on the floor, having felt like I was thrown out of bed. The first thing I thought was, ‘Oh my God, there’s been an earthquake in Tokyo.’ So I turn on CNN to see if there was a report of it, but there wasn’t. I was terrified because I had been through the North Ridge earthquake [in Los Angeles] and had a bit of post-traumatic stress. I noted the time and wondered whether I should stay up till morning but I didn’t.

The next thing I know I got a phone call saying Mr Edwards won’t answer his wake-up call. Fast-forward to me getting housekeeping to open the door, I walk in… and find him dead. [Audibly upset] The whole thing was pretty traumatic. When I was at the police station filling out the death certificate, they could tell from the state of rigor mortis that the estimated time of death was 3am. So I said, ‘Oh, you mean somewhere around the time of the earthquake?’

The coroner said, ‘What earthquake?’ I explained that I had been knocked to the floor at 3:27am, just after having this nightmare where I was the last person on Earth and the only other person was floating up like a helium balloon. I was trying to hold onto their hand but they were carrying me into the sky so I finally had to let go. So the coroner said, ‘Okay, the patient’s time of death was 3.27. That was your friend saying goodbye to you.’ I was like, ‘What are you talking about?’ To him, that happens all the time.

SP: Tell me about the night when your heart stopped.

NR: Which time?

SP: This has happened a few times!?

NR: Oh yeah. Some are less traumatic than others. One night I was just hanging out, came home, got into the elevator and somehow magically pushed the button 13 instead of my floor, which is 28. When I hit the 13th floor someone said I fell out onto the landing. I wasn’t breathing and they took me to hospital. My heart kept stopping over and over again. When I woke up the next day, the doctor stuck around just to explain how hard they had worked to keep me alive.

All I knew was that my chest was killing me and I thought someone had redecorated my apartment. He said that my heart had stopped eight times and that on the last one, he was filling out my death certificate. My heart started going again and one of the orderlies said, ‘Hey doc, we have a live one here.’ So he said, ‘Well, I guess it wasn’t his time to go.’

Another time it was probably what’s called Lynne’s Sjogren’s Syndrome, where you’re doing cocaine and your heart expires. They can start it again and there’s no dead heart tissue. I woke up in intensive coronary care next to the Shah of Iran. This was after the revolution and he had been kicked out of Iran. I used to work for his cousin in a nightclub so we knew each other. It was hilarious.

SP: You spent some time in rehab. What was the moment you decided to get sober?

NR: The last time I touched a drink or drug was 16 years ago at Madonna’s birthday in Miami. I probably wouldn’t have stopped after that night if things hadn’t happened the way they did. I made a fool out of myself. I had a beautiful date and spent the night in the bathroom with Mickey Rourke. I was also going down there to produce an artist who’s a real genius. I won’t mention his name but we had jammed together at a gig earlier and I thought I was smokin’. The next day when he played the tape for me I thought, ‘Oh my God, are you kidding me? That’s what I was doing?’ In my memory I was like Hendrix. The evidence said it sucked and the tape doesn’t lie. I needed a dose of reality because mine was all distorted.

SP: When you worked with Eric Clapton, it was a difficult time for both of you. What was it like?

NR: It was difficult for me because I was really in the throes of my addiction. Eric was Mr Sober and he had just had a really traumatic incident with the loss of his son. I was just so selfish. When you’re a drug addict and alcoholic, you think you’re having the time of your life and you want everyone to have that time with you. I didn’t get it.

I’ve only apologised to Eric once and hopefully he was smart enough to get how sincere I was. The greatest lesson I ever learned was from Eric Clapton because he never once tried to talk to me or get me sober or complain about my behaviour, at least not to me… because I wasn’t going to hear him. I thought that was brilliant and I’ve learned that same lesson, too. I don’t preach to people. I think that’s the way to be. If they want to do it, fine. If I want to do it, I’m going to do it.

SP: It’s hard to imagine anyone telling Grace Jones what to do. How do you produce someone like her?

NR: It’s a very odd job, producer. In a way the person is your boss but they’re hiring you to be their boss. So I look at my role as being their partner. On the other hand if I called up Grace Jones and asked her to sing on a Chic record, she’d do what I told her [laughs]. End of story.

As a producer, it’s all negotiation. Grace and I had fantastic arguments. Fantastic! Sometimes I would question her logic and say, ‘Grace, why would you do this?’ And she’d say, ‘Well dah-ling, because everyone else does four takes.’ ‘You want to do five takes just because everyone else does four? That’s an artistic reason? Okay then, we’ll do five.’ But I’d want to question whether there was some spirit behind it or if she was just being… jerky.

Grace is a real visionary. She understands things on a different level. She comes from the David Bowie mould, where they just see the world in a very holistic way. I like that. The more complicated the personality, the happier I am. I could sit down with Paul Simon who, as you probably know, has a reputation for being really out there. Let me tell you, I can’t be happier when I’m sitting around talking to guys like that. When I’m with Prince, I feel like I’m finally with a normal person. So that says a lot about me. I feel so comfortable among intense personalities. There’s probably no place I’d rather be.

SP: How do you make sure sparks don’t fly when you’re working with someone that intense?

NR: Sparks do fly. That’s okay. I don’t take it personally. The biggest argument I may have ever had was with Madonna. I think I have an intense work ethic but she was way more intense. In retrospect, it made all the sense in the world. She was working with my crew; there was really no one from her camp on the record. I always do that to artists: put them in a situation where they’re really uncomfortable. I need them to be out of their element. If you look at most of my records, the artist is working with people I hired.

With Mick Jagger or Bowie, they didn’t know the people they were cutting the record with. Look at the Vaughan Brothers, Stevie Ray and Jimmy — their band is the one I made up for them. We have to form a brotherhood because we have to make this song, which is not ours, wonderful by the time we leave. If I do write the song, the artist doesn’t get to hear them until they get there. When Diana Ross walked into the room, she’d never heard the songs before. When the Sledge sisters came into the studio, they had no idea what they were going to sing. You can look at the credits; that’s what I do.

SP: What does it feel like when people assume the singer wrote those songs?

NR: I think that’s great. If people think Sister Sledge wrote ‘We Are Family’ then I really have done my job! That’s unbelievable. People think Diana Ross wrote ‘Upside Down’? That is smokin’! Those records are theirs but it’s my interpretation of their lives. If you sit for a portrait painter and then look at the portrait, you might think it doesn’t look like you. To the painter, that looks exactly like you. Let’s Dance looks exactly like David Bowie.

SP: How did Diana Ross react to her portrait?

NR: In New York during the late seventies and early eighties the most underground clubs were the gay clubs and the most underground gay clubs were the transvestite and transsexual clubs. So there was this one joint I used to go to all the time near my apartment called The Gilded Grape. Every now and then you’d go to the bathroom to use it for what it was actually there for.

Maybe it was some sort of Diana Ross impersonation contest that night but I looked to my left and right and there were Diana Ross lookalikes everywhere. Then it hit me like a lightning bolt: there are a lot of women aligned with the gay community, so what if Diana could express that alignment in a song? What if Diana Ross was actually gay? That would be incredible.

So we [Rodgers and Edwards] made a song called ‘I’m Coming Out’. We’d interviewed Diana Ross about doing an album and in the course of the interview she was telling us about leaving her record company and moving to a new city; how her life was changing. So we had to convince her that ‘I’m Coming Out’ was a clever way of saying that. When she played it for a big radio DJ, he said, ‘Diana! Do you understand what this song means?’ And she came back and said [spot-on Diana Ross impersonation], ‘Um, Nile, are people gonna think I’m gay?’ I was like, ‘Are you out of your mind? How could anyone on this damn planet think Diana Ross is gay?’

If that question came up, then we really did our job right. The funny thing is she kind of was living a double life. She was in the Motown camp and the way Berry Gordy ran that company, he really was the boss. Everybody marched to his parade. Her leaving to make this record on her own was a huge statement. So it was as if Diana Ross had written that song to say thank you for the support. To this very day, she comes out on stage to that song.

Diana is the only record of hers that sounds like that because we knew we could get away with artistic murder. It wound up being the biggest of her life yet it was such a fight to get that record out. They just sound like pop songs now, but at the time they caused such a stir. Nobody liked them. The record company was dead set against it. We ended up getting into lawsuits and it was a bloodbath. Then the record comes out and flies up to number 1. The public didn’t care about all that stuff. If you put it on the radio and the phones light up, then the DJs know. That’s what happened.

SP: You gave some big artists the biggest hits of their careers, so it would make sense that you would have done their follow-up album. But that didn’t happen very often. Why is that?

NR: I think a lot of it is because those first records we did were so big. How do you replicate that? I didn’t do a follow-up with Madonna and she’s had nothing but success since Like A Virgin. If I had produced a second album and the sales were only half, you would think that I was half as good.

SP: Do you think working on a second album with Bowie takes away for Let’s Dance at all?

NR: Nah. The problem was that it was years later. I would have loved to have done the follow-up to Let’s Dance. Black Tie White Noise was under totally different circumstances. He had a label, he had funding, he was about to get married. His focus on the record was very different and he was really involved. It was more of a regular type of David Bowie record. I don’t mean that in a bad way, it just didn’t push either of us to a spectacular place. Let’s Dance cost nothing to do.

We turned it in within 17 days. When I made the demo for ‘Let’s Dance’, it was almost like a test. I think he wanted to see what I would do. I don’t think he expected me to turn what sounded like a folk song, to me, into the groove song it became. I did that right there on the spot and he was like, ‘Wow! You mean to tell me it can sound like that?’ But I don’t have any regrets about any of the stuff I’ve done. The only thing that really bugs me a wee bit is the Debbie Harry record, ’cause that should have been great. We really should have knocked that out of the park. That’s one I actually feel pain over. I don’t know how to make that up to her or me. Apart from that, everything else is the way it should have happened.