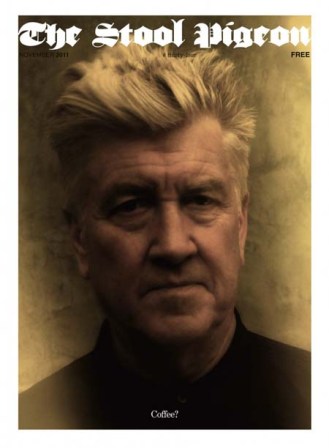

Crazy Clown Time -The Stool Pigeon

David Lynch on his life in film, wild ideas and a first foray into music

There’s a wasp stalking the room and David Lynch is on edge, trying to gauge when to swerve and when to strike. Whack! He’s sitting behind his desk in Los Angeles, wearing cream chinos and a white shirt buttoned to the collar, straining his nasally voice into a small, wall-mounted phone box. You don’t have to be there to know this, however: Lynch wears the same clothes every day. “I feel comfortable in these clothes and you can get them very dirty,” he explains. “And with what I do, ya gotta get dirty.”

His work station, on the other hand, will be a familiar sight to anyone who tuned into Lynch’s daily weather reports, broadcast for years on his official website. Near-unchanging local forecasts may have seemed an unlikely pursuit for a cinematic visionary who drinks an average of 15 cups of coffee a day. But it was the unpredictable moments, like Lynch being replaced by a masked figure whispering about eggs, that underlined the director’s status as a savant of the surreal.

Whack! The wasp retreats and Lynch’s mind comes back into focus. With a little coaxing, he’s prepared to illuminate the Lynchian aesthetic of finding beauty in decay and intrigue in mystery.

“You’re walking along,” he begins slowly, “and you look over and see some incredible violet and deep purple going to black. The light is hitting it a certain way. It’s very, very beautiful. And then you step a little closer.” He pauses, dangling the words in suspense. “And it’s a dead woman with her stomach ripped open. Now that beautiful thing has turned to absolute horror. It’s a whole ’nother ball game. But it still drew you in at first and you saw a beauty there. So as soon as something is named… as soon as a certain thing is known about a shape or a colour or whatever… it changes it.”

Normally, Lynch does not believe in explaining himself. In 34 years of being recognised as one of the most original and influential figures in film, he has revealed little. Actors are required to surrender to the obscurity of his vision without having their questions answered. His interviews are often as impenetrable as his work, clouded with riddle-like abstractions that teeter between insight and inanity. In an 11,646-word treatise on the director’s oeuvre by the late novelist David Foster Wallace, who spent time on the set of Lynch’s 1997 neo-noir film Lost Highway, the most we learned about the man behind the films was that he pees hard and often.

It’s a mystique that polarises: infuriating to those who favour linear narratives and neat endings, but intoxicating to anyone who allows Lynch to seduce their imagination.

“For some people, the world we see and live in is enough,” he says. “But once you start wondering about it, it’s just like pulling on a string with no end, almost. It’s just more and more mystery that comes out and it’s such a thrill. I think it’s because some of us are like detectives, always trying to figure out what’s going on.”

There’s an endearing innocence to David Lynch. This is a man whose speech is littered with terms like “peachy keen” and “holy jumping George!”; a man who credits never leaving childhood with his ability to dive spontaneously into creativity, going on instinct and attraction rather than intellect.

It’s easy to see why Lynch’s time as an Eagle Scout in his hometown of Missoula, Montana is the most referenced strand of his biography. His father’s job as a research scientist for the US Department of Agriculture kept the family moving around small-town America, making Lynch’s upbringing one of picket fences, camping trips and fifties cars. But visits to his grandparents in Brooklyn freaked him out: there was something sinister in the air, something menacing lurking in the subway. So began a fascination with digging beneath the surface, of penetrating the dark side.

In 1966, Lynch moved to Philadelphia, a place he has described as “the sleaziest, most corrupt, decadent, sick, fear-ridden, twisted city on the face of the earth”, and enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. One day he was painting a garden at night when it felt like the trees began to shift across the canvas, swaying in the darkness. It inspired him to attempt a moving painting for his end-of-year experimental assignment, projecting animated body parts upon a sculptured screen with three-dimensional heads. An older student, H. Barton Wasserman, commissioned Lynch to build one for his home and from there, the green lights kept coming. David Lynch was now a filmmaker.

After moving to LA to study filmmaking at the AFI Conservatory in 1971, Lynch began work on his feature-length debut, Eraserhead — a black-and-white nightmare set in an industrial wasteland — but soon found himself depressed and struggling to support his wife and child. With a loan, a film grant and job delivering copies of the Wall Street Journal, Lynch spent five years developing the film, eventually living on the set full-time while facing up to the fact that he didn’t know how to pull the whole thing together. Then he opened up the Bible and found a single sentence that unified the film’s vision. Lynch being Lynch, he refuses to tell anyone what the sentence was.

Eraserhead became a hit on the underground ‘midnight movie’ circuit — Stanley Kubrick later championed it as his favourite film — and by the time his next release, The Elephant Man, scored eight Oscar nominations, the term ‘Lynchian’ had become embedded in pop culture lexicon.

Lynch recalls this breakthrough with a satisfied “heh heh heh” but admits that the dark, dream-like take on the world that inspired the term was not strictly new. “Whatever it is, it’s always been there,” he says. “It’s in so-called ‘real life’, in all these things that we feel and sense, but I guess sometimes it might have been called ‘Fellini-esque’.”

Fellini-esque or not, turning that aesthetic into a commercial viability wouldn’t be as seamless as some first expected. As the hottest young director in Hollywood, Lynch turned down an offer from George Lucas to direct Return Of The Jedi in order to make Dune (1984), the $45 million adaptation of Frank Herbert’s 1965 sci-fi novel. It would turn out to be the biggest mistake of his career and set a headache-inducing precedent for what would become a recurring problem: artistic interference.

Years earlier, Lynch almost quit the AFI Conservatory when unwanted input forced him to abandon the film Gardenback, but this was different. Stifled by pressure and constraints from studio executives no longer sympathetic to his free-spirited approach, Lynch lost control over Dune and the film was a critical and commercial flop. Failing at something he believed in would have been tolerable, but conceding final cut felt like a soul-destroying sell-out. A lesson had been learned.

“It’s just the way it is: the number one reason people make films is to make money. That’s their goal. So whatever they think will bring people into the theatre, that’s what they want to make. Then there are some people who want to make money and win an Oscar. So they’ll put their attention on that and that will lead them down certain other roads. But then there are some people that just get certain ideas and they fall in love with them and they have to make those things. They’ve got a reason, just like the others, and they just want to see this thing on the screen. But the financers, they say, ‘You are crazy. This is a crap idea! No one’s going to go to the theatre.’ And so they don’t get very much money.”

Fortunately for Lynch, being contracted for two more films (including a scrapped Dune sequel) under producer Dino de Laurentiis meant he was allowed to make Blue Velvet (1986) relatively undisturbed on a meagre budget. The film’s portrayal of a perverse underbelly eating away at the idyllic facade of all-American suburbia earned Lynch another Oscar nomination, setting him up to expand on the same motif for his biggest commercial success, Twin Peaks.

Lynch’s two-hour pilot episode about the murder of a homecoming queen was unexpectedly picked up by ABC and commissioned as a seven-part series that would alter the face of television. Drawing nearly 20 million viewers in the US alone, the show’s charms became inescapable: The damn fine coffee and cherry pie, the log lady and the one-armed man, the backwards-talking dwarf and the prophetic giant, the Red Room within the Black Lodge, the swaying traffic lights and brooding woods, the charisma and humour of its oddball characters, Angelo Badalamenti’s hypnotic soundtrack and the mystery of who killed Laura Palmer. Lynchmania had taken over. Even the Queen of England was hooked, reportedly snubbing a specially prepared performance by Paul McCartney so she wouldn’t miss an episode.

“Y’know, (Twin Peaks co-creator) Mark Frost and I talk about it sometimes,” says Lynch, breaking into a laugh. “I think the big surprise is how this little place with these few characters travelled around the world and how it can be experienced and felt the same way 20 years later. There’s no way to figure it. In fact if you could figure it, then there’d be a formula to it and people would be making it so that every show would have that thing. Everyone would be a billionaire, or whatever. It’s just funny how it caught on. I don’t know what the ingredients are. It just seems like we tapped into somethin’, like a gift.”

But the show’s meteoric rise brought familiar anxieties. With a second series commissioned, network executives insisted that Laura Palmer’s killer be revealed —something Lynch believed should never happen. In the face of mounting scrutiny, he turned his attention to filming Wild At Heart, which would win the Palme d’Or at Cannes, while a series of directors took over the show. New characters and sub-plots were introduced, often being weird for the sake of being weird, draining the series of momentum.

“It was almost like David went onto other things and left it in the hands of people who were trying to do Lynch-isms,” says Charlotte Stewart, who co-starred in Eraserhead and played Betty Briggs in Twin Peaks. “Only David Lynch can do Lynch-isms, because he doesn’t think like other people. You can’t imitate him. His concepts are unique: the sound, the setup of the picture. He’s an artist and knows exactly what he’s looking for, right down to shadows and odd shapes that you may not be aware of while watching, but which still make you really uneasy.”

Though Twin Peaks pioneered the ‘water cooler effect’ whereby people couldn’t resist discussing clues and theories after each episode, its real strength was in creating the impression that you were visiting a world rather than just watching one on TV — an effect that still inspires Twin Peaks festivals and themed parties around the world.

But since returning for the show’s finale as well as a prequel film, 1992’s Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, Lynch has made just four more films. With the exception of 1999’s appropriately named The Straight Story, a linear narrative based on real events, these releases boasted less resolution and more fractured fantasies than ever before.

A Lost Highway soundtrack featuring David Bowie, Trent Reznor and Marilyn Manson drew a younger audience to Lynch’s back-catalogue in 1997, providing the perfect springboard to launch another TV show two years later. Lynch had tantalised executives at ABC with his ideas for Mulholland Drive, a dream within a dream set in a Hollywood netherworld. But when they saw the two-and-a-half hour pilot, questions were stirring nervously: could he clarify the characters’ motivations and leave room for romance? Did he really need that close-up shot of steaming dog shit? Or the heart-stopping scene where a face black with fungus emerges from behind a dumpster?

After ordering all pauses and puzzles to be removed, ABC’s vice-president of drama programming determined the fate of the series by allegedly watching the edited pilot from across a room at 6am while making phone calls. He had just one question: “What the fuck is it?” The project was shelved and left in limbo until a French film company stumped up the funds to adapt it into a standalone film that would earn Lynch another Oscar nomination and a Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2001.

The film’s hazy eroticism and maze of parallel worlds has endured so well that Club Silencio, a new Mulholland Drive-inspired bar in Paris, has been designed to Lynch’s every specification, right down to the saltiness of the peanuts. But the source of such inspiration, Lynch says, is often misunderstood.

“I have only gotten a couple of ideas from night-time dreams but it’s the dream logic that I love. It’s such a great thing for cinema to express. In that world, there are different kinds of rules for time and place and sequence.” Lynch stops to clear his throat, his voice softening as he considers how this approach renders his films notoriously inconclusive.

“A certain amount of closure in a story is very good. It can’t all just be open-ended, unless it’s a pilot for TV. You want resolutions, you want some closure but at the same time I always say you want room to dream. I use this example, which I think is one of the greatest, and that’s the film Chinatown. It has plenty of closure, but then the guy says, ‘Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.’ And… zhoo! You just zoom out and it’s such a great thing.”

Anyone who has seen Inland Empire (2006), a three-hour experimental montage of loosely connected ideas, might find this difficult to believe. Shooting without a script freed Lynch to follow his intuition, like spontaneously deciding the film needed a 16-year-old one-legged girl and a spider monkey, but many felt its unconscious coherence amounted to a dream-sequence too far. Though Lynch retained final cut as well as the rights to its DVD and distribution, the film received mixed reviews and speculation has been growing that it will be his last.

“When I made Inland Empire, it was kind of unusual that I shot with a little digital camera. And look at what’s happened since then. Everyone’s doing it. It’s a total digital world now, really. The film business is changing and drifting towards what happened to the music business, I feel. I’ve been kinda just watching and seeing which way things are gonna go.” When pressed as to whether he could leave things as they are, he adds: “We’ll just see if these ideas come in. I feel them. It’s like I’m in a big house, in an inner room with a little fire going in the fireplace, and I feel the ideas outside in the window-well, scratching.”

Lynch is obsessed with chasing ideas. Now 65 and on his fourth marriage, he spends most of his time puttering about his compound in the Hollywood Hills, stubbing his American Spirit cigarettes on the workshop’s cement floor while drilling holes and hammering objects into three-dimensional, Francis Bacon-like artwork.

Music crept into the frame when he teamed up with Danger Mouse and Sparklehorse for 2010’s Dark Night Of The Soul, an album for which he sang on two songs and contributed a limited edition book of his photography. Then one day later that year a melody popped into his head and, strolling into his on-site recording studio, Lynch put down an auto-tuned, Euro-pop-like ditty called ‘Good Day Today’ with the help of his sound engineer, Big Dean Hurley. What he came up with in the months after, however, was a stream of bastardised blues for the unhinged: songs of stalkers, psychos and scoundrels. The resulting Crazy Clown Time is Lynch’s first collection of sounds without long-time collaborator Angelo Badalamenti to guide his muse, though the album inhabits the same esoteric space as ‘The Pink Room’ (from Fire Walk With Me). As Lynch alters his voice between songs, he affects them for melodic monologues worthy of Blue Velvet’s Frank Booth and Wild At Heart’s Bobby Peru. The tracks unfold as scenes that spur your imagination into collaborating, driven on by the sound of the filmmaker’s creeping, reverb-heavy guitar, immersing you in that familiar journey to the world of Lynch.

He chortles with approval at hearing this. “Yes! You are doing it, Cian! That’s really beautiful… Fantastic!”

All of these characters, he says, float towards him as fully formed entities: he imagines them walking into a room, then simply observes how they talk, what they’re wearing and the way they act. “And you can just start saying what they’re saying,” he says. “You just write that down!”

Steer Lynch towards the subject of channelling ideas (“catching the big fish,” as he calls it) and he motors away in an uninterrupted whirlwind of enthusiasm. “When that light bulb goes off, Boom! It’s like, ‘Hello?’ It’s like electricity, it’s like white light. So much comes in one instant. Now it may not always be a thrilling idea, but they all come like that and once in a while — whammo! You fall in love.”

Blue Velvet, he maintains, came in a quick succession of fragments: red lips, green lawns and Bobby Vinton’s version of the song ‘Blue Velvet’. Once he could picture an ear lying in a field, that was it — he had the makings of a subversive masterpiece.

“When you get an idea like that,” he says, “it’s like you’re goin’ down the road and you find a really beautiful rock. That’s great that you’ve found a beautiful rock — and you can polish it up and put it in a window — but the rock isn’t yours. Really, a lot of this has nothing to do with me. The most I think we are is translators.”

That process hasn’t always been so easy, though. Lynch once suffered from so much anxiety, anger and depression that he deemed his state of mind a “suffocating rubber clown suit of negativity”. But after seeing his sister’s demeanour improve as a result of Transcendental Meditation, Lynch gave it a try and has been meditating for 20 minutes, twice a day, without fail since July 1973. Believing it infuses every aspect of his life with clarity and creativity, he setup The David Lynch Foundation: a charity that funds the teaching of meditation among at-risk populations.

Yet in the 2007 documentary Lynch (One), filmed during the making of Inland Empire, Lynch can be seen growing agitated and slipping into flunks, muttering asides like, “I’m so depressed. I don’t know what I’m doin’.”

“Now when did you see me lose my temper in there?” he says, chuckling heartily. Well, there was the moment where he snaps, “Fuckin’ morons, everywhere!” from behind the camera — hardly the action of a poster boy for serenity. “Talk about a world with no rules!” he says, roaring with laughter. “After you’ve been meditating for a long time, you can still get really sad. But the sadness can’t stick to you. You could be crying your heart out about something, but then two minutes later you’re on to something else. You can get really mad. But at the same time you sorta see a humour in yourself getting angry and it doesn’t eat you like if you weren’t meditating. And that’s the secret: it saves you from poisoning yourself with anger or sadness or depression or fear or whatever. It saves a lot of that from killing you. It frees you to enjoy life more and more. You don’t just become a goody two-shoes on the set and everybody gets kisses and cookies after we finish shooting!”

For someone who seems to fetishise darkness and violence, Lynch insists that his signature themes are a reflection of the world at large rather than any conflict within. Hailing from the picturesque heart of America doesn’t stop him from seeing a disturbing side to life, he believes, nor does he have to suffer for his art. In Lynch’s mind, the tortured artist would be an even greater, more prolific talent if they could orchestrate anger and fear in a way that lets the characters do all the suffering.

So after all these years of leading by example, how many people truly understand David Lynch? “Oh, only a handful,” he says, his infectious laugh thundering back. “Naw, I’m just jokin’ ya. I’m not that hard to understand. The secret, though, to understanding anything is that it’s tied to consciousness… It’s a huge, huge, giant — giant — thing we’re involved in.”

There’s another Lynchian twist coming here — and you can tell he’s gearing up to leave us hanging in confusion. But he can’t. Not this time. If he wants to get mystical, surely he can do it in a way we can clearly understand, in a way that breaks down the meaning of life in one simple explanation. “Well,” he says, barely pausing. “It’s like high-school. You start one place, you move through and then one day you graduate. Not every human being has the same amount of consciousness, but everyone has the potential for infinite consciousness. It just needs unfolding. And if you can do that, then there are zero problems.”