Christy Moore

Interviews: 2011 / 2013 - The Irish Times

Christy Moore is thinking about the songs he never wrote. The ones that remained unfinished, the ones that resisted polishing, the ones that failed to do their subject matter justice.

He can feel certain stories nagging at him to be preserved in music – Savita Halappanavar, the Corrib gas controversy and Johnny Carthy, a 27-year-old man shot by gardaí – but their channelling has proved elusive.

The trouble is, Moore couldn’t be less cavalier about the craft. This is someone who will spend years honing songs he didn’t write himself, obsessively reshaping them into the right fit. You can see signs of the process all over Moore’s music room at his home in Monkstown, south Dublin: a clutter of potential set lists, post-it notes, ornaments and instruments. Just last night he wrote a new verse to ‘Delirium Tremens’, a song he composed 28 years ago.

“It’s difficult,” he says. “I’m working on a bunch of new songs now and none of them are coming. I may never write another song... and it doesn’t matter if I don’t because the ones I have are great.”

Moore has never been prolific. By his own count, he has written around 100 songs since he began recording in 1969, 45 of which he reckons are decent. For the first time, he has gathered that output in one place: a triple album entitled Where I Come From. The artwork, already hanging on a wall outside, depicts an atlas of inspiration, a blending of pathways that have shaped his life.

“My songs are scattered across so many albums that you think: ‘Wouldn’t it be nice to have them as one body of work?’ If I die tomorrow, some record company might just bang them all together. At least I feel it’s done now and my family have a collection of my songs; they won’t have to go rootin’ through 30 albums to find them.”

Moore being Moore, all the songs have been recorded anew. Those that didn’t measure up have been scrapped; those that felt timeless have been pared back to shine unhindered.

“It’s been an interesting journey to go back through it all because while you move on, the work stays there,” he says. “Take a song I wrote in the ’70s or ’80s: all these years later I’m a much older man and I hear things differently. Some of the things I did back then would make me wince now, even the way I sang. My melodies are very basic; my guitar playing is limited, so there was an opportunity to improve certain songs musically and some of them are now much better than the original recordings.”

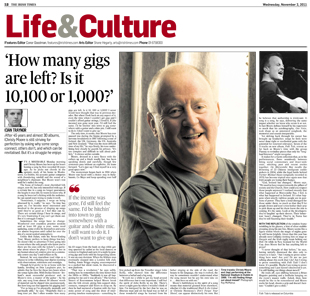

Moore, 68, is sitting at his desk, a guitar and bodhrán by his side, taking his glasses on and off as he recounts a life in song. Having grown up in Newbridge, County Kildare, he initially became enamoured with rock’n’roll – Bill Haley, Elvis, Buddy Holly – until the sound of the Clancy Brothers eclipsed everything else. They weren’t just singing about Ireland, he says, they were speaking his language.

“When I started singing 50 years ago, there was no such thing as songwriters. Think about all the songs handed down through the millennia – it just didn’t dawn on me to view myself as a songwriter. Songs were things you collected, cherished and passed on; I would travel to Galway or Roscommon or Manchester just to track one down.”

Moore pulls out a photocopied issue of Time Out from 1969, his fingers running over the listings until he finds his name. Three years after leaving his job at a bank to immerse himself in the English folk club circuit, he played on the same bill as Peggy Seeger and Ewan MacColl in London. The awe instilled from sharing a stage with a songwriter of MacColl’s calibre “sowed a seed”, Moore says. But it was through the “journalistic approach” of Woody Guthrie (and later Bob Dylan) that he learned to find a voice, to chronicle matters of consequence and to subtly expose injustice.

The opportunity to do so arose in 1978 when Moore visited the H-Blocks of Maze prison in Northern Ireland, meeting with paramilitary prisoners observing a ‘blanket protest’ over their rescinded political status. That inspired ‘90 Miles to Dublin’, its title a nod to the frustration of seeing an issue so close to home eliciting apathetic silence. Evidently, Christy Moore’s first composition touched a nerve: the song sold out and was promptly banned.

Though the craftsmanship would evolve, that same strand of social commentary courses through Where I Come From, not just charting critical events in Irish history but picking away at the scabs they left behind.

There are songs for Bloody Sunday, Veronica Guerin, the Birmingham Six, the Stardust nightclub disaster (another song of Moore’s that was banned), the Holocaust, Haiti, Anne Lovett, Giuseppe Conlon, abuses of the Catholic church, Irish volunteers in the Spanish Civil War and the strip-searching of women in Armagh Gaol. Taken together, it’s difficult to think of another artist who not only refuses to shy away from taboo topics, but tackles them with thought-provoking compassion.

“There are subjects on this collection that are very important to me,” he says, lowering his voice as he leans forward. “Even though it mightn’t reach that many people, it’s all there. They’re little monuments and I’m glad they’re marked.”

Moore gets up and walks over to something else he wanted to memorialise, gesturing at a photograph of himself outside the home he grew up in. “I often think of that house, that life, that world,” he says. “It’s totally gone from the face of the earth but it’s in the [title] song and I get transported back there when I sing it, even if only momentarily.”

Those moments of transportation define Moore’s live experience. It’s the rousing craic, sharpened wit and electric atmospheres evoked in the anthemic ‘Joxer Goes to Stuttgart’, the ever-evolving ‘Lisdoonvarna’ (now updated to include Swedish House Mafia) and ‘Welcome to the Cabaret’, an icebreaker developed to settle nerves and woo crowds. He records every concert – “I treat it as a special entity, not a place for promotion” – mindful that every spontaneous dip into the repertoire could produce an unforgettable one-off.

Moore’s songbook is steeped in the lore of nights gone by, its liner notes blotted with references to darkened snugs, lethal concoctions and crippling hangovers. He began drinking at an early age, recognised a problem at 23 and finally swore of his dependency after a concert at Moorefield GAA Club in 1989, the same night he wrote ‘Moorefield’ – a song he hasn’t touched since.

Getting back on the road and playing that material to revved-up crowds must have been difficult, one would imagine, for a recovering alcoholic. “It took about 10 years before I could be comfortable with it,” he says, nodding. “A drunk person in the room used to really rattle me. I’m much better at livin’ with it now, though. I very seldom get angry. It’s all part of the experience.”

If there’s any question whether Moore’s social commentary is still as relevant, still as biting, then there’s arguably no better gauge than the debate his most recent composition, ‘Arthur’s Day’, has helped stoke. It’s a clever takedown of what he sees as an insidious marketing ploy and, despite the mention of Twitter and Mumford & Sons, the song slots seamlessly into his catalogue of well-worn classics.

“Arthur’s Day was just so horrible and ugly,” he says. “The problem is the drink industry is seeking to convince young people that the only way they can enjoy themselves is by having a relationship with their product. Musicians are then being exploited to move that product but it’s dressed up so well that people get incensed if they’re deprived of this thing.” It’s a difficult one to argue, he acknowledges, but it’s a debate worth having.

“I think now that the cynicism of the PR campaigns are finally being noted, politicians will think twice before standing beside Diageo PR people to advertise the next Arthur’s Day. Still, I did encounter severe anger and criticism for opposing it.” He stops himself, smiles and shrugs, offering a hint that perhaps he’s not quite done with the craft of songwriting just yet. “But so what? I’ll take that. It’s not the first time that happened and it won’t be the last.”

Christy Moore - The Irish Times (2011)

It’s a miserable Monday morning and Christy Moore has been up for hours honing a song he first recorded 16 years ago. Sitting in the upstairs study of his home in Monkstown, Co Dublin, his acoustic guitar is competing with thundering rainfall and the sound of a neighbour’s chainsaw. But Moore won’t rest until he’s nailed it.

At 66 years old, the focus that drives Ireland’s most cherished folk singer has only intensified. If a certain line in a song no longer guarantees the laughs it once did, he wants to know why. If a song he

loves isn’t clicking with the audience, he can spend years trying to make it work.

“Sometimes I suppose I verge on being obsessed by it, really,” he says. “As time has gone on, I’ve become more interested and involved in the process of shapin’ up songs until they’re as good as I feel they can be. There are certain things I hear in songs and it’s very frustrating if you can’t get them out. But it’s a struggle I enjoy.”

Sometimes the songs have to change. Weathered over countless practices and at least 60 gigs a year, some need updating, some evolve by themselves and some are almost forgotten until called for over the din of a sweat-soaked atmosphere.

Unlike Bob Dylan’s Never-Ending Tour, Moore prefers to keep things low-key. He doesn’t like to advertise (“I love going into a town where the only people who know you’re there are the ones with the tickets”), is particular about where he plays (“I’ve got a bee in my bonnet about art centres; give me a community centre any day”) and refuses to fly.

Instead he sees marathon road trips as a chance to write rollicking tour diaries teeming with observations, witticism and nostalgia. Though he’d prefer to be at home with his family, strolling Dun Laoghaire pier, he admits that he lives for those two hours when the venue lights dim. With Declan Sinnott – a figure Moore regards as a master of the guitar and Ireland’s most successful producer – by his side, any song from almost 30 albums’ worth of material can be dipped into spontaneously. But how long can that appetite for gigging last?

“For as long as I’m physically, mentally and spiritually able,” he says. “Hopefully that’s a long time yet. But I often wonder how many gigs are left. Is it 10, 100 or 1,000? I never would have thought that way in previous decades. But when I look back on any aspect of it, even the time when I couldn’t get gigs and I couldn’t afford guitar strings, I loved it. If [the income] was gone next year, I’d still feel the same. I’d be hitchin’ into town to gig somewhere with a guitar and a shite mic. I still want to do it. I don’t want to give up.”

The only time, it seems, that Moore has ever paused was during the hiatus prompted by a nervous breakdown in 1997 following a tour of Ireland, the UK, Germany, the US, Australia and New Zealand.

“That was the most difficult time of my life,” he says firmly, his tone underlining how closely he guards his privacy. “It’s too complex and difficult to talk about publicly.” A silence settles outside.

Moore, dressed in a navy fleece with the collars up and a black woolly hat, has been speaking slowly and carefully, though few sentences pass without an expletive. He leans forward. “Let’s just say I find myself in a very good space now.”

The momentum began back in 1966 when Moore was faced with a choice: stay in Ballyhaunis, Co Mayo and keep spending over half his £8 wages from the bank on digs while getting spurned by cailíní at the local dances, or venture to England and earn £4 a night by powering jigs and reels with his burgeoning talent. It was an easy decision. When the Kildare man eventually stepped into a London folk club, finding Annie Briggs singing unaccompanied to a packed but silent room, he

discovered a new platform.

“That was a revelation,” he says softly, recounting how he remembers the time better than the 1980s or ’90s. “Suddenly it was all happening for me and it was all new.” The Grehan Sisters of Roscommon helped Moore break into the folk circuit with support slots, contacts, transport and floors to sleep on. By then he had nurtured a fixation with the hypnotic power of song and the draw of interpreting timeless masterpieces – something he first picked up from Traveller singer John Reilly, who showed him the difference between a ballad and a big song.

“It took me a while to get my head around that difference but it was important. I still feel the spirit of John Reilly in my life. There’s never a night goes by where I wouldn’t think of him. I’m intrigued by

the fact that he was an illiterate man and yet his head was so full of these wonderful songs he learned from his father singing at the side of the road; the beauty in his language, the way it evolved, the way he sometimes wouldn’t understand what the song meant but he put his own take on it... that lives on with me.”

Moore’s faithfulness to the spirit of a song means that material gleaned from elsewhere, whether it’s the traditional ‘Black Is the Colour’ or Christie Hennessy’s ‘Don’t Forget Your Shovel’, can appear

distinctively his own. But he believes that authorship is irrelevant. A song is a song, he says, delivering the same impact whether we know who wrote it or not. In fact Moore defines himself by his repertoire so much that his autobiography, One Voice, took shape as an annotated songbook, the memories and sounds inseparable.

Yet delving back through his career has brought up headaches: songs he feels were never done right or overlooked gems with the potential for renewed relevancy. Seven of the 11 tracks on new album Folk Tale retreat as far as Moore’s time with the seminal group Planxty to revitalise pieces that only his “long-haul listeners” might recognise.

It makes for a warm collection that, as in his performances, flows seamlessly between biting social commentary and Joxer-style craic, stitching past and recent events together. ‘On Morecombe Bay’ recalls the drowning of 23 Chinese immigrant cockle pickers in 2004, while the legal battle behind 'Farmer Michael Hayes' (originally recorded in 1978) has become topical once again now that many Irish people are losing their homes.

“God, Ireland has changed,” Moore says. “We used to have respect towards the pillars of society and the Church. How could you respect those people anymore? I realised recently that what happened at Morecombe Bay, I feel, is what has happened to Ireland. It’s what happens when utterly ruthless people are in positions of power.

They have a total disregard for those under them, so much so that they’ll let people drown and won’t even bother their arse to pick them up and let them know the tide is coming. It’s the same. Look at the developers: they’re laughin’ up their sleeves. Their behaviour hasn’t changed. They’re in Nama but they’re still flaunting their wealth.”

With the reflection of the window frame twinkling in his glasses, a hint of silver stubble creeping along his jaw line, Moore seems like a figure within whom the magic of nights gone by still burns brightly. Given that this year has already seen Coldplay inviting him on stage at Oxegen and the Irish rugby team belting out ‘Ride On’ while in New Zealand for the World Cup, does Moore feel he has anything left to prove?

“I never thought of that before,” he says, having initially dismissed the idea only to return to it later. “Am I trying to prove something here now? Are you? Or are we just talking about this work that I do? Am I trying to prove something with Folk Tale? I don’t know. It’s possible. Maybe I am trying to prove something and I just haven’t discovered it yet. I’m still finding out things about meself.”

He trails off, eyes shifting between a Brian Maguire painting and a bodhrán hanging on the room’s mauve walls. Asked, then, how would he like to be remembered and Moore cocks his head, shoots a grin and doesn’t hesitate: “Couldn’t give a shite.”